Scott Matthewman - The Reviews Hub ****

Scott Matthewman - The Reviews Hub ****

When slavery was abolished in the 19th century, the businessmen whose livelihoods had depended upon enforced, unpaid labour faced the issue of how to continue to find workers.

In Mauritius, a small island in the Indian Ocean and a territory of the British Empire, the answer was indenture – the mass import of working men (and some women) from India, in a scheme that the British government sanctioned as a “great experiment”, but which had so many similarities to the slavery it was replacing. The mass economic migration transformed Mauritius into Britain’s premier sugar producer, but at what cost to the island and its society?

Border Crossings’ devised piece takes the Mauritian experience as its focus, structuring its exploration as staged recreations of rehearsal room dialogues and exercises, as well as imagined scenes of Mauritian people of the time.

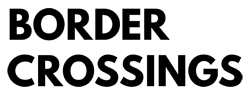

This technique allows some of the potential pitfalls in the approach, from casting choices to who gets to tell these stories. Thus we see Tobi King Bakare on the phone to his agent as he frets that, as the only black cast member, he’ll be expected to play the slave roles, while Hannah Douglas (also on the phone, to a friend) sheepishly admits that the story of importance to Asian peoples is being directed by a white, middle-aged male Oxford graduate.

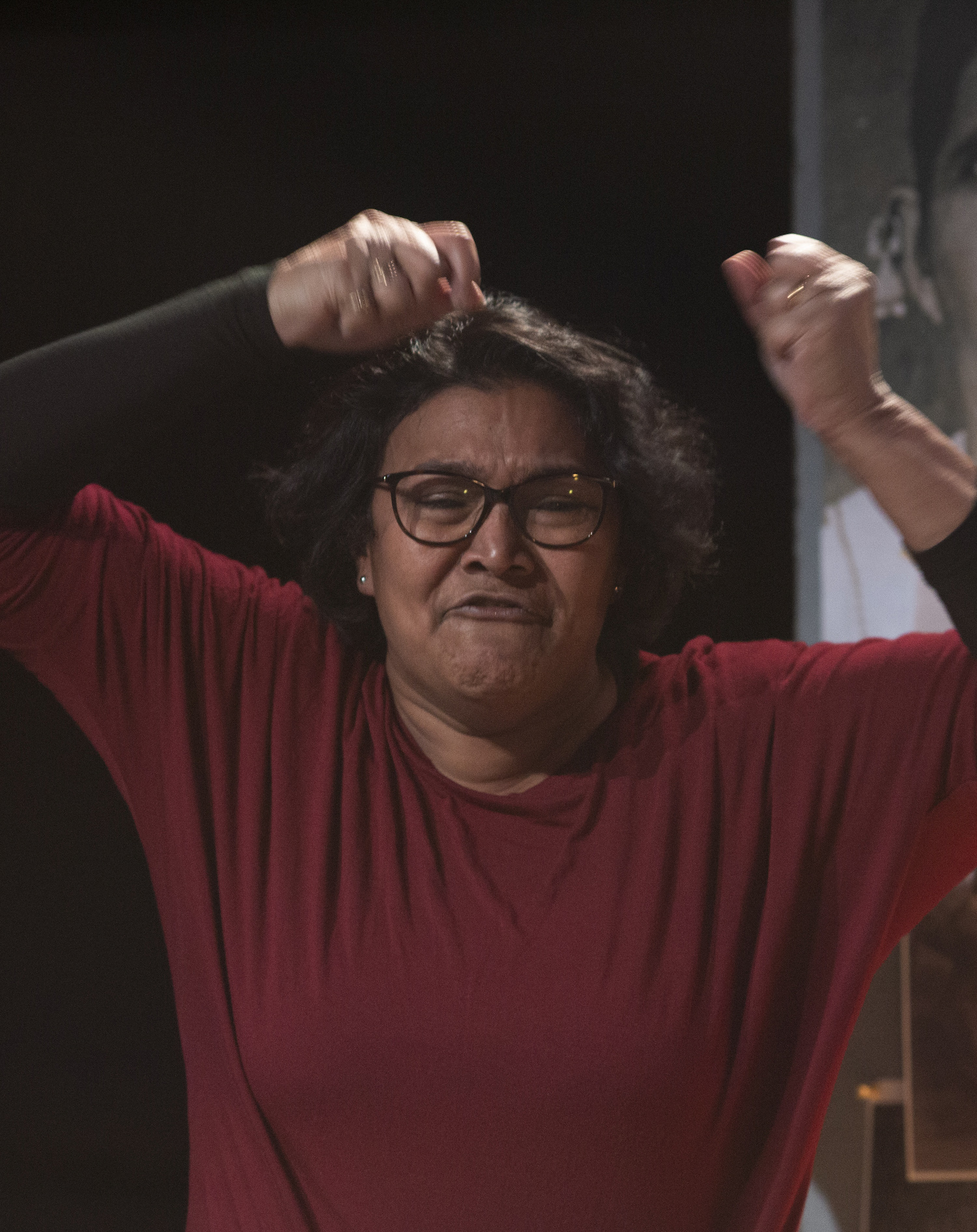

Two of the five-strong cast, Nisha Dassyne and David Furlong, both come from Mauritian families. Dassyne in particular impresses as her exploration of her ancestors’ stories causes her to question the veracity of the family folklore. Stronger still is her furious, visceral explanation of why the Indian immigrant population feel such shame – sparked, uncomfortably, by how they felt treated as if on a par with the slaves they replaced, when they themselves saw themselves as better.

But when it comes to slavery, shame fans out – such as when Douglas’s family tree is discovered to go back to a man who himself owned slaves. We are expected to use the passage of history as an excuse to lose the shame; it rarely happens thus.

And it is this inexorable connection between the past and the present which fuels THE GREAT EXPERIMENT’s greatest moments. The dichotomy of wanting to distance oneself from one’s ancestors’ mistakes, while retaining a sense of their culture – something that slaves and the indentured were assumed not to do – is a recurring theme.

So too is how much one should expand the parallels of slavery and indenture to other parts of the world and other times. The climax of the show comes in a furious loop, Tony Guilfoyle’s points about the treatment of the 19th century Irish – and the perception from others that expanding the discussion might somehow diminish the experience, and importance, of black people’s history – creating a circular argument that reflects so many divisive discussions today.

The only way of breaking those circular arguments is knowledge gained from listening. By focussing on an island whose history has rarely featured in our collective consciousness about slavery and indenture, Border Crossings’ haunting stories provide us with the tools to explore our global history, our shame, and to recognise where the 21st century needs to learn from the past.

MAKING GHOSTS ACCESSIBLE - Daniel Nelson - One World

THE GREAT EXPERIMENT is one of those plays that justifies itself simply by being staged.

The title refers to the British Government’s 1842 decision to open Mauritius to Indian labourers to produce sugar, following the official abolition of slavery seven years earlier.

A memorial in Port Louis records what ensued: the arrival of 453,063 Indians, to be followed by another 1.5 million to other colonies, Fiji and South Africa. “It transformed the demographic make-up of those territories and continues to have global ramifications,” says historian Marina Carter’s programme note for the Border Crossings theatre company’s 90-minute dramatisation of those epochal events.

“Was this an act of breath-taking hypocrisy, or a stroke of genius?” Carter asks. “Was indenture merely slavery under another name or more akin to the contemporaneous migrations of Irish and other impoverished white working-class groups? Historians have long wrestled with these questions, some of which seem peculiarly relevant to modern debates about ‘free movement’ and ‘ immigration controls’ in the Brexit era.”

Who in this country knows about this massive upheaval of humanity? Hardly anyone. That’s not surprising given how few have more than a rudimentary knowledge about Britain’s role in – and huge economic benefits from – slavery or about colonialism.

Even if this play were awful, Border Crossings would win plaudits for spreading the word about events that still reverberate, not least as Indian communities in a number of former British colonies fight for their rights and are involved in political, economic and social struggles. But he play is not awful: it’s moving, powerful and hard-hitting.

It tackles this vast and complex issue on two fronts, giving faces and stories to people lost to history and dramatising the efforts of the actors, several of whom have Mauritian connections.

One of them, deviser and performer Nisha Dassyne - born in Mauritius, studied in India and worked in UK – has said in an interview: “Working on THE GREAT EXPERIMENT, I’ve had to visit the ghosts and memories in my family. They have become more concrete, more human, more accessible.

“The connection to my ancestors isn’t just something to talk about anymore – it’s a real connection.”

The historical, informational elements are simply and deftly handled, but it’s when the play within the play gives voice to controversies over race and identity that the piece catches fire. At first it seems that contemporary resentments and stereotypes may be pushing historical education off the stage, but a moment’s reflection makes you realise that racism was an integral part of THE GREAT EXPERIMENT and that THE GREAT EXPERIMENT was an integral part of today’s racism.