If there is one genre in contemporary Indian writing in English that seems to have been consigned the status of a poor cousin of fiction and poetry, it is that of theatrical writing or drama. It is not as though it is a new phenomenon, playwrights have always been not as popular (unless you write and produce light commercial bedroom comedies or sit-coms) as novelists or poets.The reasons of course are obvious, plays need to be produced and performed, and more often than not, that is hard to achieve easily. Then the English language theatre-goer tends to be largely restricted to a certain metropolitan audience. Moreover, even when the plays are produced, they tend almost always to be the ones penned by foreign playwrights. Is it that there are not enough Indians writing plays in English?

In the last five years or so, there have been very few Indian playwrights who have seriously written in English. The two that immediately come to mind are: Gopal Ghandi who has written a fine historical verse-play Dara Shukoh (New Delhi: Banyan Books); and Mahesh Dattani whose Final Solutions and Other Plays (Madras: Manas) and Tara (New Delhi: Ravi Dayal) have earned praise. Dattani's lively and provocative play BRAVELY FOUGHT THE QUEEN toured three venues in England recently, the first time that his work has been performed outside India. Produced by Michael Walling's company Border Crossings and codirected by him and Dattani, this play included a cast that combined artists from India, the British South Asian community, and the British white community.

Briefly, the script is in three acts, titled 'Women', 'Men', and 'Bravely Fought the Queen'. The play is set in Bangalore of the 1980s and 1990s. The narrative is “centred around an Indian family, in which two brothers, the co-owners of an advertising agency, have married two sisters. The women remain at home much of the time, where they look after the men's ageing mother Baa. Much of the play's tension comes from the interaction between the enclosed, claustrophobic, female world of Act I and the male world of business in Act 2. The fact that both sexes are living lives based on fantasy is cruelly exposed when the characters confront each other in Act 3, and the realities of their lives emerge. The homosexuality of one of the brothers, the crippled daughter of the other marriage, Baa's continued presence - all of these facts are concealed in the uneasy world which the characters inhabit. The play becomes a plea for humanity and for tolerance”. It is equally a cry for the acceptance of Indian values that are shifting, where tradition and contemporary clash, confuse and create a new social landscape. Dattani writes with a pungency that is skilfully disguised, employing language that resorts to clarity and sharpness, one that pushes the limits of the spoken word and the pregnant silences in between.

“It is because of this multi-layered reality in the play that the production uses naturalism as only one of many styles,” remarks Walling, "The house and office are suggested in the setting, but the play moves constantly away from them into an internalised reality”. The set in particular and the mis en scene in general have obviously been thought through with subtle minimalism. At the Battersea Art Centre in London where I saw the play, the squarish stage space used was in fact a small studio with the audience viewing the action up-close at a level just below the sight line. This created a sense of extreme intimacy with the actors, and in the scenes of high drama, a feeling almost of being overpowered and engulfed. A video screen placed high on the rear backstage on the right projected images that were clearly alluding, obliquely and directly, to sexuality, feminity, inverted masculinity, protest and struggle. In Act 1, we view a black and while video film of a bare bodied man (Dattani himself) wet in the monsoon rains with the camera slowly panning and hovering indulgently over his flesh. In Act 2, there is a woman in a similar setting but wrapped in a sari. And in Act 3, we see film footage of Govind Nihalani's Tamas, as the political tension in the film mirrors and refracts another kind of tension within the family and business relationshihs, enacted in full fury.

A variety of theatrical and technical modes are effectively employed. The sacred space of the stage is defined, redefined, and altered simultaneously by superb lighting design and by the actors who map out different territories, both central and peripheral, as they slow-march on the edges of the frame whilst the parallel narrative continues on the centre stage. Stylised movements, clearly inspired by Bharatanatyam and Kucchipudi dance forms are used to convey movements, transitions, continuations within the text and the sub-texts. Dattani has edited his original playscript heavily. He says, “Western theatre has the sophistication of filling the sacred space with silence and stillness. 'That is the major contribution made by Western society to our theatre”.

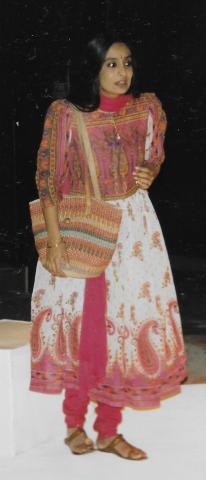

The acting, particularly by Suchitra Malik as Lalitha and Adlyn Ross as Baa, was outstanding. The studio, though intimate and effective accommodated a very small audience for a production that most certainly deserves a much wider audience and reception. Dattani and Walling have teamed up fluently, without the pitfalls and cliches of an East-West unison, to provide a creative work that is powerful, tightly written, produced with a craftsman's care, one that evokes feelings that are both funny and sad, but ultimately human and moving.

Sudeep Sen

June 1996

(Article originally published in The Gentleman)